How to Make Pretty A Non-Priority

What defines beauty? Our bodies? Our skin tone? Or our cultural expectations, wrapped up in media exposure and an absence of role models of color. As Mash-Ups, sometimes our standards of beauty collide in confusing and complex ways. As parents, we want to clear the confusion for our children, especially our girls. But as our Filipina-American Mash-Up Alexis Diao learned, perhaps the next generation of Mash-Ups has a clearer picture of our beauty than we do.

My parents did not raise a wilting daisy. As a young girl, I never went through a princess phase. I rejected dolls and the color pink. I did not play sports. I was not a tomboy. I was a latchkey kid who read books, liked being outside, and was painfully shy. As far as beauty went, it wasn’t a priority. Being beautiful was self-evident as far as my parents were concerned: Your rice is white, but you are not. You are beautiful, let’s eat.

Not that I was spared the painful pubescent years of insecurity and self-loathing. I was steeped in that, and it was awful. Even now, as a full grown woman, those feelings of insecurity bubble up and it’s still awful. But as a young child, I accepted my parents opinion of me as truth. Their word was law, and I was pretty because they said so.

And I think I was lucky in that way. Because although “pretty” was a pleasant trait, it wasn’t the ultimate ideal. They wanted a daughter who worked hard, got good grades, showed kindness and respect.

It’s a very un-Asian thing to hold yourself with self worth without apologizing for it.

It’s a very un-Asian thing, I think, to be taught to hold yourself with inherent self worth without being taught to apologize for it. (Note: to hold, despite how you actually feel.) At least in the Filipino culture, it seems as though many of the women I knew always had something negative to say — about the “mangoes” in their upper arms, about how their skin was too dark, or their eyes were too insic or “Chinese.” As far as I could tell, the ideal was to be skinny, dressed in expensive clothes, have wide eyes, and light skin. In other words, to be a thin white woman.

Except for my mother. She has always been an anomaly compared to other Filipina women in the community. She is outspoken, unapologetically sharp in both mind and tongue, and sometimes she really pisses people off. She is confrontational and frank: traits that Filipinos don’t take kindly to. The general rules of engagement are: If you have something to say, you really shouldn’t say it. You should have someone else say it, like the person closest to that person or a diplomatic third party.

But my mother? She doesn’t abide by these rules, much to the dismay of others.

I think her inclination to directness makes her more American than Filipino, and she probably likes the country more because of it. She is beautiful. When she was my age, she weighed 90 pounds sopping wet. She had light, curly hair and was always stylishly dressed. I remember when I was a young girl, other kids’ moms looked tired with unbrushed hair, big t-shirts and pedal pushers. Mine looked like a beautiful, small woman. She wore 90’s sundresses, heels, shoulder pads. She had this perpetual bra strap escaping her shirt. Admittedly, I sometimes wished she looked like everyone else’s Mom, but like I said, she doesn’t abide well by others’ rules.

Over brunch recently, I asked my mother about her boldness, and how she taught me to be confident in the face of both Southern and Asian expectations of beauty. Why didn’t I go through a princess phase? How did you make sure I wasn’t obsessed with being pretty?

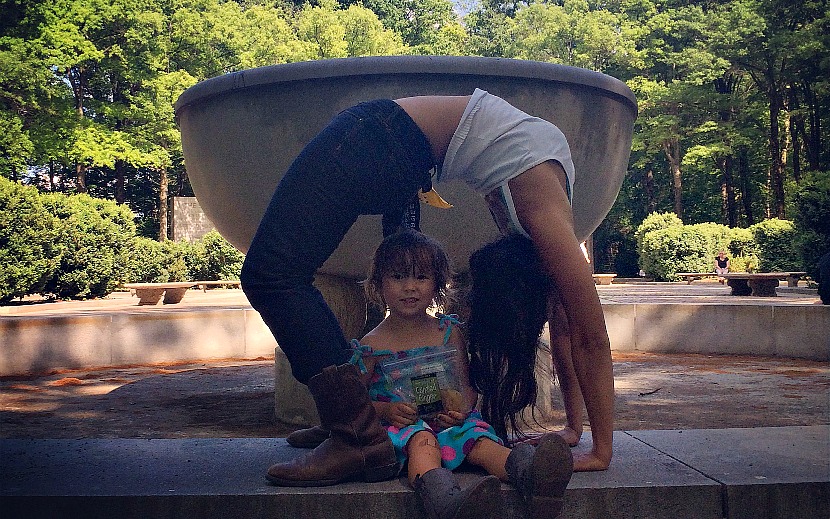

She said it wasn’t look that she praised, but ability. Because being pretty is nice, but it’s not practical. In retrospect, this makes sense. She encouraged me to to do everything I could. Rather than admiring my petite hands, she pushed me to do things with them. My hands are small (I wear a size 3.5 ring), but I can stuff, debone, and roast a chicken like a pro; load a gun; grow a garden; start fires; break a man’s clavicle; handstand; and comfort with ease my crying daughter.

This is the beauty I try to show my daughter.

Because, despite my best efforts, my American daughter is going through a princess phase, and I am coming up empty-handed with how to fight it. She wants to watch “Frozen” every day, play with the white baby doll in class and — help me Lord — read Cinderella. She wants to have the same experience many of her classmates are having, and as a mother I want to provide that to her.

But there is a line, a very fine line you walk as an olive-skinned first-generation Filipino-American Mash-Up Mom of a fair-skinned, Swedish-French Canadian-Filipino Mash-Up daughter. I want her to share in similar childhood experiences as her peers, but I don’t want to leave her vulnerable to industrialized standards of beauty and strength. Disney is not always healthy for our self image. I know the damage that bogus heteronormative standards, and the lack of representation of minorities in mass media, especially female minorities, can do to women of color.

My daughter is also white. Will people even know she is Asian?

And yet – my daughter is also white. She has fine, reddish-brown hair that streaks blonde in the summer. Not the thick, black hair I have. I’m not sure what it will mean for her to grow up half-Filipino and half-white. Will people even know that she is Asian? Will they even care? How much will she identify with being Asian? Does she need Asian role models the way I did?

When she wants to play with toys or watch movies that feature white, female characters, she at least in part identify with that character, in a way that I did not. She looks like these characters, and may find strength in them.

Growing up, there was not much in the way of strong, Asian-American figures to model myself after. One could counter that there was Mulan, and I love me some Mushu, but Mulan was Chinese, not American. As far as Asian-American characters go, there was the Yellow Ranger and arguably, Chun Li. But nobody wants to be the Yellow Ranger. It was all about Kimberly, the Pink Ranger. She was blonde, popular, liked by the boys, and the lead character. My white classmates took turns playing the Pink Ranger. And I, of course, was typecast.

Now that I’m on the other side of childhood, I wonder what box my daughter’s peers will try to put her in. She’s mixed, not just Asian, and all of the factors that will eventually trickle into her mental nexus of what makes beautiful — clothes, the male gaze, the female gaze, fashion, fitness — will likely be colored by her background. I worry.

Maybe I don’t need to. She’s only three years old, but she’s pretty articulate. Recently I asked her about beauty.

“Sol, are you beautiful?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because you are.”

“Is Mama beautiful?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because I am.”

From the mouths of babes. Maybe I can learn from her.

Yes, you are beautiful. Read more:

Skinny in America, Fat in Korea

Going Natural: Leaving Relaxers, and Pain, Behind

Hair Revelations from Mash-Up Ladies