Matthew Salesses On Bootstraps, Zombies, And Doppelgängers

Ever wonder if you can parent and publish books in a pandemic? Our Korean-American Mash-Up Matthew Salesses proves, well, that at least he can. Matthew is the author of novels The Hundred Year Flood, and Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear, and his newly released book Craft in the Real World explores alternative models of craft and writing workshops, particularly for marginalized writers. His previous books include I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying; Different Racisms: On Stereotypes, the Individual, and Asian American Masculinity; and The Last Repatriate. Matthew (he/him) was adopted from Korea and raised in the U.S. He took some time to chat with The Mash-Up Americans about occupying multiple dimensions, the wisdom in K-Dramas, and making sure his kids finish their meals.

So you’ve been home with your kids, ages 9 and 4, while also teaching remotely through the pandemic. What’s been keeping you all going?

We eat a lot of frozen food. A lot of pasta, ramen, a lot of different kinds of soup, doengjang jigae. And we all like meat. I’m just trying to make them continue growing. But they’re doing their best not to. [Laughs]

Do you and your family have any traditions for starting off the new year?

I do actually. I’m very attached to the new year for some reason, even though it’s completely arbitrary. I’m attached to anything that’s like, here’s the new start, we’re handing this to you. You get a new start here on this day. Usually what we do is clean up the house. My wife used to say, how you spend New Year’s Day is how you spend the entire year. You know, as if the day itself gets extended across the year. So we try to spend it with each other and do things that make us feel good.

![[Image Description: Photo of a Korean American man with short black hair and gold-rimmed glasses, looking into the camera. Behind him are two children. One of the children has long black hair and a pink shirt, and is looking inquisitively at the camera. The other child is wearing a striped gray and white shirt, and has their mouth open and eyes closed in excitement.] Photo Courtesy of Matthew Salesses](http://www.mashupamericans.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MatthewSalesses_021921_EDITED_4.jpg)

You have published two books in this wild year. How’ve you been staying creatively fed?

I’ve been watching a lot of Netflix. I hate all monsters and scary things, except for zombies. I think it’s because they’re slow and really predictable and just wander straight at you. They’re very single-minded – I like that about them, you know what’s coming. Right now I’m reading The Lying Life of Adults, and it is amazing. If only we could all write like Ferrante! I also watch a lot of K-Dramas. One of my favorite lines in K-Dramas is the idea that “you’ve made me like you, now you need to take responsibility for that.” Like I didn’t just randomly fall in love with you, you did things to make me think that I should like you. But also, I think it goes along with the idea that things are not so agency-based. Sandra, one of the characters in Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear, talks a lot about fate, right, and thinks about things as already established, already in the works, and having to take responsibility for things, even if they’re not things that you think you personally have caused.

What was it like launching Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear this past fall, in the midst of the pandemic?

I sometimes wished we had pushed it off for awhile. With novels, there’s no rush, but I’d already pushed it back a couple of years, because my wife died and there was a lot going on. I think unless your book really takes off, a lot of people are a little disappointed in how their sales performances were in the pandemic. And then you miss out on a lot of the fun things about launching a book, like seeing friends and meeting new people — they’re all in-person things, eating in different places.

Also, Zoom fatigue is definitely real. I think it’s probably just seeing yourself and then being like, oh, man, I need to look like I have it together. [Laughing]

I’m appreciating the parallel to the doppelgänger effect.

Yeah, it does seem like there are two of you there. Like, you have to keep track of two different people, even though they’re both yourself.

There’s a line in the book when the character Yumi is saying to Matt Kim, “All your sentences start with ‘I’.” And he responds, internally, “The first rule was to know your audience.” Did you have a particular audience in mind as you were writing the story?

I was really trying to write toward Asian American people around my age, maybe literary people, and writers. And it seems like people have really liked the book. I just wish it reached more of them. Originally it was called The Murder of the Doppelgänger, and it was a murder mystery of the self. I started out writing trying to get at that murder mystery market. But of course, my own concerns are more with Asian American stuff, and disappearance and visibility, and adoption. It took me like two years to try to figure out what I wanted to be doing with the book at all. I was trying to write a best-selling novel, and then a thriller, and then it turned very literary, and I was very glad that I had already sold it, because I thought nobody would ever buy this novel now. [Laughing] But I was hoping at least that it would have some depth of impact with the readers that it did reach, and that’s been nice to hear.

The main character repeats different sayings to himself throughout the novel, like, “There’s nothing to fear but fear itself.” Is there a bubbemeise you find yourself drawing on as a parent?

Have you heard of fan death? [Editors note: HAVE WE EVER.] A lot of Koreans believe, really seriously, like my wife believed, that if you sleep in a room with a fan going and there’s no window open, then you will die in your sleep. And I would be so upset that I couldn’t turn on the fan [laughing] because my wife thought we would die. In general though, I think I try to counter common sayings with my kids.

What are the ones you try to counter?

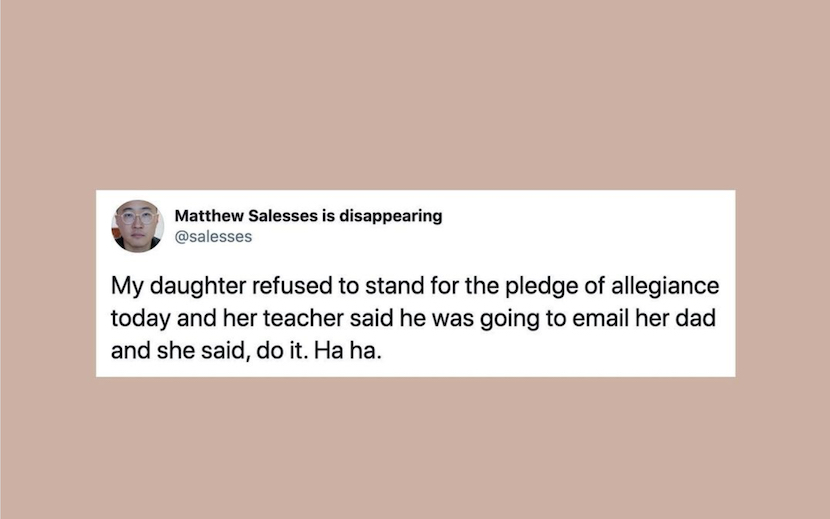

Especially ones that have been passed along as wisdom within the system, like “pull yourself up by the bootstraps,” for example. Or, sometimes the things that my daughter who’s nine gets taught in school. She’ll come home and be like, “This seems like the opposite of what you told me, it doesn’t seem right to me.” And so we have conversations about deprogramming her [laughs], but I’m hoping that she’s more skeptical than maybe the average white person.

One of my big goals with Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear was that it would be able to break down established meanings of things. That’s why there’s so many repeated sayings, because we already know that these are things that are programmed into us. I mean, I’m writing in English, and I think that I need to be able to break it down first, in order to create new associations. With Craft in the Real World, too, I was trying to break down established things and hopefully make room for new things.

Yes! By the time this interview’s published, Craft in the Real World will indeed be out in the real world. In Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear, the main character Matt Kim is experiencing this persistent duality of identity between himself and his doppelgänger, as he becomes increasingly certain that he is disappearing. And in trying to understand that double-consciousness, a third consciousness begins emerging.

That reminds me — I teach a lot on facilitating discussion in the classroom, and so I did this training with the Chicago School of Public Thought. And someone was talking about how she was working in a high school classroom. And they were debating things, right? And she asked, “How many times in debate have you ever seen somebody change their mind?” Everyone was like, “Oh, never.” And she said, “The nature of the debate is just that, right? Like, there’s no third thing. And everybody, if they weren’t polarized before, has to become polarized in order to take part in the discussion.” And that was really interesting to me to think, like, the mode of discussion that we’re taught as kids in school is basically debate. But it’s not actually a productive space.

I think a lot about why people are not convinced when they see facts, or when somebody they really care about, like their kid, comes out to them or something. These huge moments that should change people’s minds, if anything is going to. Once I wrote this whole essay about how differences are actually a good thing and we shouldn’t try to pretend we don’t see them, or say, like, “Oh, you’re a good Asian because you’re like a white person,” basically. Or, what I got a lot was, I don’t even think of you as Asian. And my parents acted like that a lot. And I said something in the piece about my dad saying, like, “I don’t think of you as Korean, I just think of you as my son.” And he wrote me on Facebook and said he had read the entire essay and said, “Well I just still think of you as not Korean, but just my son.” I was like, “Those things, they’re not separate, you know, they can be in the same space.” But people are able to just dissociate one thing from another pretty easily, I think.

You’ve written about transracial adoption for Codeswitch, and you’ve included themes of adoption in your fiction writing. Sometimes the work of writers of color or Mash-Up creators’ work is often assumed to be autobiographical. Has that been your experience?

Yeah, I get that a lot too. I think we get forced into these spaces, but then we feel responsible to occupy the spaces, too. When I published The Hundred Year Flood, when it was about to come out, they asked me for comps to put on the back, like other adoptee novels. And I couldn’t think of any other Korean adoptee novels. So I started to ask Facebook and Twitter, and nobody I knew could think of any. There was like one maybe, from a very small press, and then there were some from European adoptees. And so I just hadn’t realized that they weren’t out there. And then I felt bad that there wasn’t like more in the book about adoption. Cause if I had known how few stories there were out there, I would have probably felt more responsible to include that kind of thing, even though the book has adoption-related stuff.

I think we get forced into these spaces, but then we feel responsible to occupy the spaces, too.

So it’s like, we get pushed into that position, but we also know the scarcity, in terms of representation. We know what it’s like out there. And so we choose to be in those spaces, too, I think, not only for ourselves, but for other people, who maybe grew up like us.

In Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear, some of the characters’ occupations, like marketing, for example, create opportunities to talk about assigning value, or hacking the system, from a programmer’s perspective. Those discussions highlighted how much the questions of identity in the book really are relational and circumstantial — they’re about how Matt Kim is being perceived. How would you describe how you mash-up?

The fact that I’m adopted is very strange for me because it’s both very obvious but also I find myself always having to say that I am adopted. And then worrying about representation and my name, it’s a French name. So it seems like a white person is writing this article… So I always have to say I’m adopted, like “this is a lived experience.” So that is a thing that’s always kind of there. You know, these days, a lot of it is about fatherhood and writing and being Asian American and surviving, maybe [laughs]. Yeah, actually thinking about this in terms of the pandemic is interesting, too. Like all the terms we use to describe ourselves are all kind of productivity-based, like your career, or the things that you’re doing. It’s either the things that you do, or the ways that other people see you, the roles that you have to play.

What’s been making you hopeful these days?

I’m pretty pessimistic, and I think that helps me survive in a way. So I don’t have a lot of hope. But I have hope in the kids. Not only my kids, but the students that I have. I think the people in this generation, if they can all be lumped into one generation, I don’t really understand how generations work… But it does seem like the students that I have now are just so much smarter, and have so much more of a feeling of responsibility toward the world, and are so much angrier and so much more with it, than I was as a student. And so that, I mean, that does give me a lot of hope. They’ve kind of been forced into it, and they’re hyper aware of it because they’re gonna grow up into all the environmental damage that you know, people older than us have caused. So they have to be, but it also does give me hope.

What would you say to the younger generation of writers and creators who also feel a sense of responsibility?

Take care of yourself, and take care of other like-minded people. One of the best things in my experience going through the MFA and PhD program, was that you find people, and if you take care of each other, those people really will be there for you later in life.

![[Image Description: Photo of a Latinx man in the middle of a performance. He is shirtless and has a green pair of mesh underwear over his face as he looks down towards the ground. Bright pink and yellow pieces of fabric are wrapped around his arms. In the background are two other performers, one sitting on the ground and one on all fours. Behind them are seated audience members observing the performance. There is fabric and other items strewn across the performance space floor.] Photo Credit: Ian Douglas](https://www.mashupamericans.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/MiguelGutierrez_031921_EDITED_1_CREDIT-IAN-DOUGLAS-248x194.jpg)