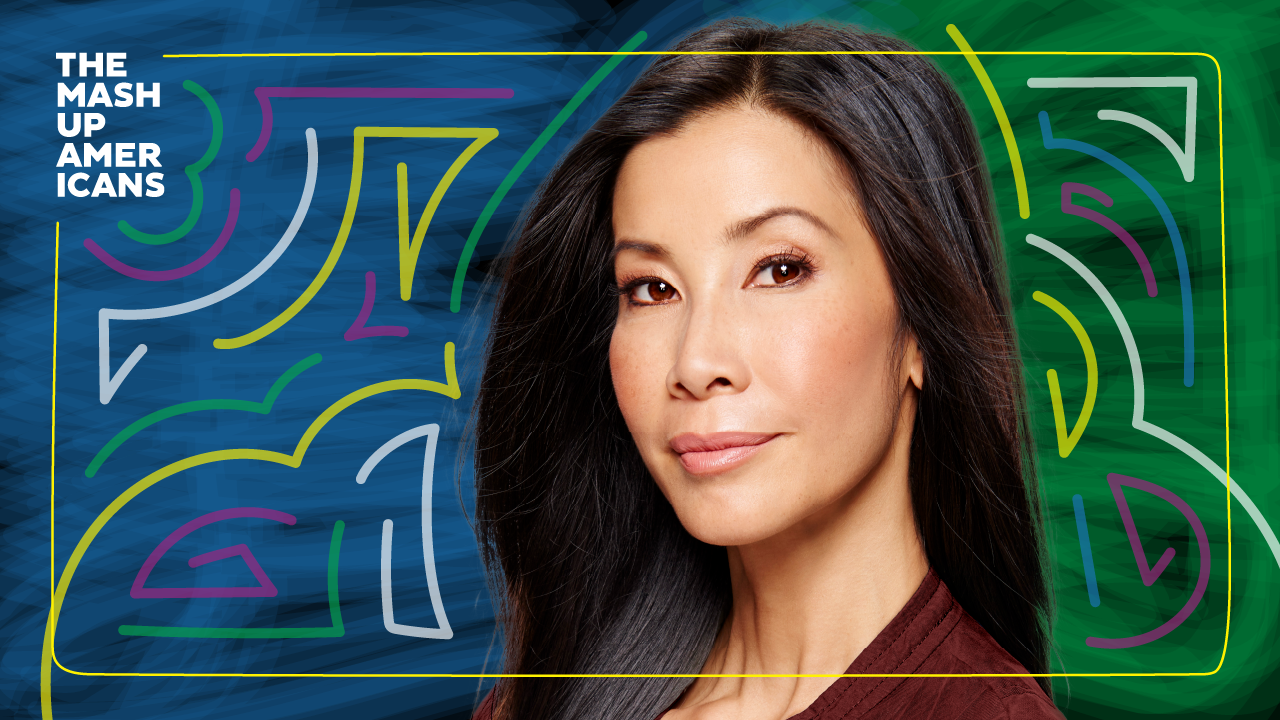

Lisa Ling Lives With Her In Laws (And It’s Great)

Healing is a b*tch. How do we break the cycle of generational trauma? Lisa Ling’s got some answers (and, yes, it might involve plant medicine). The celebrated journalist, executive producer, TV host, author and mother sits with Rebecca and Amy to share about her journey to heal her familial bonds, her compassion for her mom, and her hard-won friendship with her religious Korean mother-in-law (IYKYK).

It is really hard, because so many of us have these deep scars. And it’s impossible to think about our own parents, not as our parents, but as a similarly stunted child who didn’t get what they needed from their parents. And when you really stop and think about it, our parents didn’t just have parents that weren’t able to show affection. They went through wars…they went through and experienced things that in our wildest dreams we can’t even imagine…

…And it’s not their parents fault, right? It’s this trauma that has lived with us intergenerationally that we can’t pinpoint. But it makes sense that, you know, if you don’t have a model for how to do it, how would you ever know how to do it?

Lisa Ling

Make sure to check out Lisa’s top lessons in how to live with your in-laws.

An Edited Transcript of Our Convo:

Rebecca Lehrer: You are listening to The Mash-Up Americans.

Amy S. Choi: Hey, I’m Amy Choi.

Rebecca Lehrer: And I’m Rebecca Lehrer. And we are The Mash-Up Americans.

Amy S. Choi: Rebecca?

Rebecca Lehrer: Yeah?

Amy S. Choi: You live with many generations of your family around you, like vertical, up and down, horizontal. Northeast Los Angeles is actually like Lehrer Angeles.

Rebecca Lehrer: That is correct. I’m nodding very hard. True.

Amy S. Choi: And it’s like one of the great delights of my life has been falling in love with you and your family and with LA. I’m not going to say your husband, Neil, because I was in love with him before, but the way that you have so many layers of family and being in your home is like everybody’s coming in and out and there’s oftentimes dogs that are not your dog that are in your house.

Rebecca Lehrer: I know. Rest in peace, Lola. Rest in peace.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, Lola, she really had a good life. She did.

Rebecca Lehrer: She did. She really did.

Amy S. Choi: But I know your parents’ dog and I knew her whole sickness story.

Rebecca Lehrer: Yes.

Amy S. Choi: Just the fact that I have been adopted in and we’ve kind of all adopted each other, your parents have adopted me. Every time your dad meets a new Korean person, he texts me because he’s excited.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, yeah. Which is often.

Amy S. Choi: It’s not infrequent how often Michael texts me about a new Korean thing that he’s learned. But what-

Rebecca Lehrer: Yes, he is a kimchi…

Amy S. Choi: Oh, God. Michael, Love him so much. Mia, love you too. But I think your family does it with so much grace. And it’s also not easy, as somebody who does not have that. I’m really close with my cousins, but those are relationships that I really worked hard on as an adult. I’m close with my sister, but my parents are far away. There’s a lot of shit going on with intergenerational stuff. Having that interconnectedness that you have with your family, it doesn’t come without a lot of work and also, it’s hard. And I think still that’s one of our ultimate rules for living a beautiful life is embracing the complexity of interconnectedness and doing the work to allow that to bloom.

Rebecca Lehrer: Absolutely.

Amy S. Choi: It’s hard and beautiful. And that’s also maybe one of the mantras of a mashup life.

Rebecca Lehrer: Absolutely. How do you act with grace? How do you process all those things? It’s so beautiful and I’m really lucky to be part of a Jewish community that I really love. And our rabbi, Susan Goldberg, gave a really beautiful sermon this year during the high holidays about interconnectedness and really how interdependent we all are. And one of the things she said that really… Well, she really pointed out, it’s hard, too. Sometimes it’s really easy to just be kind and sometimes it’s really hard-

Amy S. Choi: Sometimes people are assholes. That’s a fact.

Rebecca Lehrer: …but being in community is the work, is what life is made up of. And it’s also one of the things she said was we are not individuals, we’re actually generations. And that she wished for all of us to experience the deep hope of our interconnectedness. So that is something that I’m really taking to heart this year is this idea of the hopefulness of what it really feels like to be human, which is needing each other.

Amy S. Choi: That is so beautiful and we have learned so much about healing through generations from our guest today, our friend, the legend, Lisa Ling.

Rebecca Lehrer: Lisa Ling. Lisa Ling is a journalist. You have seen her on CBS, CNN. She has so many shows of her own. She’s done everything, from embedding with notorious biker clubs to covering the LRA in Uganda to the humanitarian crisis in North Korea to hosting daytime talk show with her stint on The View.

Amy S. Choi: She’s so amazing.

Rebecca Lehrer: She truly is. And she has transformed her relationship with her family through so much healing and plant medicine in a way that has opened up her life to living with her-

Amy S. Choi: Korean mother-in-law.

Rebecca Lehrer: Korean mother-in-law, her own mom, her sister-in-law, and just squeezing all the love and life out of the chaos that interconnectedness brings.

Amy S. Choi: Total inspo for me personally, for everybody, and we are in awe and we’re so excited to have her here today.

Rebecca Lehrer: Here’s Lisa. Okay, Lisa.

Lisa Ling: Okay. Here we are.

Amy S. Choi: Here we are.

Rebecca Lehrer: So, Lisa Ling, how do you mash up?

Lisa Ling: How do I mash up? I feel like that is a perfect way to characterize my entire life. Even on the way over here I am thinking about so many different aspects of my life. I mean, in one week I went from this black tie gala where Oprah and Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicole Kidman and Kim Kardashian were in attendance, and then the next day I’m back at my home in LA and my kids are coming into my bed unable to sleep at 4:00 in the morning and I am stressed out. I’m trying to clean up all the laundry that is strewn all over the place and-

Amy S. Choi: And you’re like, “How did this just get here?”

Lisa Ling: Yeah.

Amy S. Choi: “It wasn’t here 12 hours ago.”

Lisa Ling: I mean, I was gone for less than 24 hours and it’s just like Armageddon at home. But then several days before I went to that black tie gala, I was embedded in a little town in Colorado and I was observing three generations of women at a psilocybin retreat. They were all drinking psilocybin tea and off on another planet. And so I feel like the word or the term mashup is synonymous with my life and has been for the last more than a decade.

Rebecca Lehrer: I feel like, well, you are a living embodiment of mushiness and mashups in so many ways. One thing we wanted to ask a little bit about at the start before we get into current life is give us a little of your life, growing-up life. You grew up in Sacramento, is that right?

Lisa Ling: I grew up in a little suburb of Sacramento called Carmichael, California.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, my god, what a name.

Lisa Ling: Carmichael, yes.

Amy S. Choi: Carmichael.

Lisa Ling: When I was growing up, it was otherwise known as White Michael because it was such a non-diverse, diverse community. There were so few Asian families.

Amy S. Choi: How did your family end up in White Michael?

Lisa Ling: Well, it’s interesting because my grandparents came to America in the late 1940s and they both happened to speak perfect English. My grandfather was educated in the United States, got his MBA in the United States. My grandmother studied in England and they came here with high-level degrees, but they couldn’t get hired to work in finance and so on. So they ended up living in a converted chicken coop and eventually salvaging enough money to open a Chinese restaurant. And because they spoke such good English, they were able to move away from the predominantly Chinese community in Sacramento to Carmichael, to White Michael, and open the first Chinese restaurant ever there. So that’s how I ended up in Carmichael.

Rebecca Lehrer: So you grew up in White Michael, and then, are both of your parents Chinese American?

Lisa Ling: My mother is Taiwanese American and my father is Chinese American. Yes, these days it’s very, very important for me to make that distinction. Actually, not these days, I have made that distinction for a long time. But because there were so few Asians growing up, I really didn’t know much about my Taiwanese identity either. It was just so much easier to say Chinese. I was already different because I was Chinese, so to have to explain that Taiwan was a different country at the time was just way too much for a little girl to be able to handle.

Rebecca Lehrer: Were the grandparents who opened the restaurant your paternal or maternal grandparents?

Lisa Ling: Paternal, so those were my Cantonese Chinese American grandparents. My Taiwanese grandmother, my mom’s mom, she didn’t speak any English. Both my grandparents passed away when I was in my early 20s. And people always ask me, “What’s your greatest wish? What’s your biggest wish?” And my wish would be to have one more day with both of my grandmas because they were so special and important to me. And there’s so many things I want to ask them, but particularly my Taiwanese grandmother because we couldn’t speak to each other. There’s just so much about her life that I will never know.

Rebecca Lehrer: I also think that’s a thing about grandparents, those of us who are lucky to actually have gotten to spend any time, you’re very lucky while you’re developing as a young person and they’re declining as an older person, that there’s a moment where you’re at a place where you are open or able to engage really beautifully with them and they’re still lucid and engaged because then you could have intimacy, which is not always the case with somebody older.

Lisa Ling: Well, my mother and my husband’s mother became grandparents to my kids very, very late. I have a seven-year-old and my husband’s mother is 91, and she loves the fact that she has these young grandchildren who can come over and they want to be there because she says most of her friends have grandkids who are all grown up and they just don’t have time to spend a lot of time with her-

Rebecca Lehrer: Well, they would be great grandkids at this point-

Lisa Ling: … at 91.

Rebecca Lehrer: … because there’s too many layers, right.

Lisa Ling: Exactly. But on the other hand, I don’t know how much time she has left on the earth. I mean, she’s 91 and she’s been having some health challenges. And so the notion that my kids won’t get to spend significant amounts of time with her makes me so, so sad. And so therefore, both my mom and my mother-in-law are at our home, because they live a couple of blocks away from us, almost every single night.

Amy S. Choi: We have many questions.

Lisa Ling: There is a lot of food that’s cooked every single night. There is a lot of advice being doled out to Paul and me every single night, and it’s highly overwhelming every single night. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. Paul once said, “Is it too much?” It’s like the advice will not stop coming. It’s not even advice. It’s like they don’t directly say, “Why are you feeding them this?” It’s sort of like… these sounds.

Rebecca Lehrer: Can you do a difference? Is there Korean mother-in-law versus-

Amy S. Choi: The guttural. It’s a more-

Lisa Ling: The Korean is definitely more guttural, as Amy can attest to.

Amy S. Choi: I’m very familiar with that sound.

Lisa Ling: I wasn’t even doing it justice. It’s more like, “Mmm.” It’s like this deep nasal, throaty, guttery-

Amy S. Choi: There’s some mucus moving around.

Lisa Ling: Yes, yes.

Amy S. Choi: Jo Koy actually has a great interpretation is that an older Korean person always sounds like they’re stoned when they’re talking to you, judgy and stoned.

Lisa Ling: It’s like, “Yeah, nay…”

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, my god.

Amy S. Choi: There’s something that we have been discussing a lot, and this has been kind of thematic over the year, but it has been coming up in a lot of these conversations as we think about what it means to build a good life, about the stories that we tell ourselves and the narratives that we build and whether or not they’re true and how stories get interpreted through generations.

And so it’s really something magical that your girls are young, but they’re not so young that they’re going to have to rely on your story of your mother or Paul’s story of his mother. They’re going to be able to have living stories themselves that they have created with each of those people that they can carry for the rest of their lives. It’s so magical that you’re creating this for them. Because I think that with a lot of mashup families, because of language divides, because of literal physical divides, I mean now it’s so much easier because I’m… 43?

Rebecca Lehrer: No, 44.

Amy S. Choi: I’m 44. Me, growing up, it wasn’t like I could FaceTime a cousin in Korea. That was just not a reality. So if you were not with your family-

Rebecca Lehrer: No, if you ever talked on the phone it’d be like you have to just say hello to your grandma and then hang up for us because it was so expensive.

Amy S. Choi: It’d be $22.

Lisa Ling: Yeah.

Amy S. Choi: So I totally appreciate that you have just been like, maybe this is madness, but this is our madness and you’re giving your daughters this gift.

Lisa Ling: Yeah. And they are still very young. I mean, my daughters are 10 and seven, so they will have those memories, but they’ll be just shorter. They’ll be a little more limited. But nevertheless, it’s so, so important for me to allow them to just have some.

Amy S. Choi: I always find it amazing, as somebody who does not live close to their parents, and my sister, who I’m very, very close to lives on, it’s silly, in New York City, it’s a mile and a half, but she may as well live on the other side of the world because she’s in Manhattan, and I’m in Brooklyn, is that, are there invitations extended? Do you make a plan with either of the moms or are they just present?

Lisa Ling: Oh, no, they have keys to the house. They’re in the house before we even get there, sometimes. No invitations are extended. Our domain is their domain.

Rebecca Lehrer: I will say, as a person in a couple where it’s just my family who’s over all the time, I really appreciate that my husband’s just like, “Yeah, they just walk in.” The gate opens to the side of the house and there’s just always some member of my family, brothers, parents, whoever, maybe even a cousin, but you both. That’s nice. There’s equal opportunity invasion, which I kind of love.

Lisa Ling: Oh, it gets better. It’s not just the grandmas who are in our house. My husband’s sister lives in our house.

Amy S. Choi: Oh. Oh, hi.

Lisa Ling: Hi. And my cousin, Dorothy, when I travel or have to work, she sometimes comes and stays in the house, as well. It’s really sad for Paul, and we have a female dog, because Paul has just been estrogened out.

Rebecca Lehrer: That’s why he has to do all these trips. He’s like, “I got to go escape these people.”

Lisa Ling: He’s got to go hang out with the dudes. So it’s not just the grandmothers, they are the loudest, but the house is always full of people. And my sister-in-law, who I absolutely adore, she doesn’t have kids and has a very successful career and a house, a beautiful house not far from us, but she was recovering from a heart condition, a heart operation a number of years ago and came to recover at our home. And my kids, they love her so much. She’s my kid’s godmother and she plays with them.

I am not a good player, but she does arts and crafts with them. She will bake with them anytime they want. She plays and plays. And so after she recovered from her surgery, my husband and I were like, “Will you please just stay here? Rent your house out. Please stay here.” And so it’s been great. When my kids wake up in the morning at 5:00-

Rebecca Lehrer: That’s so fucking rude.

Lisa Ling: They know not to come into our room anymore. They go straight into Coco’s room. And the name Coco is really cute because auntie in Chinese is “gugu.” And in Korean, it’s “como,” and so they kind of combined it and call her Coco.

Rebecca Lehrer: That’s a great mashup.

Lisa Ling: It’s a great mashup.

Rebecca Lehrer: I love it so much.

Lisa Ling: But she is known by everyone now as Coco, which is a combination of Chinese, Korean ideas.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, that is the cutest. So it seems that there’s also a lot of intention, even to say to Paul, “You know what? There’s not that much time, so let’s just make the most of this chaos while it’s here.”

Lisa Ling: Well, also, our culture in America just doesn’t value our seniors. And it was inadvertent that our lives kind of ended up this way, but when you think about how people in Asia live, they have multi-generational homes. And while I never thought that I would live that way because I grew up in America, it’s so beautiful. It’s chaotic and loud, but it’s so beautiful. I love having so much family in my kids’ lives and in my life all the time.

Rebecca Lehrer: I actually have a question for you about, as you’ve been in therapy and you’ve mined a lot of your thoughts about yourself and how you exist in the world, and your husband is doing similarly, with these wonderful ladies in your home who may or may not be the cause of some of those things, when they’re with your children are there moments where you’re like, “I’m extremely triggered by this right now,” when they’re say something to your… Although they’re different with grandkids, but are you ever like, “This is why I have to go to my bedroom,” because this mother’s saying something?

Lisa Ling: Yes. So Paul and I, though our lives were obviously different and we are of different cultures, we had some similarities in our upbringing. My parents were divorced when I was seven, and my mom moved to Los Angeles, and so she was not in the house most days because she was geographically quite distant from me, and my dad worked all the time. So it was my grandma who was in my house who was taking care of my sister and me.

Rebecca Lehrer: This is the British educated one?

Lisa Ling: Yes, yes. And Paul’s parents, they worked all the time. And he was an athlete and he played every sport.

Rebecca Lehrer: Readers, he’s very tall and handsome.

Lisa Ling: He’s very tall.

Rebecca Lehrer: Strapping.

Lisa Ling: Yes. And he’s-

Amy S. Choi: If you want to know if Lisa Ling’s husband occasionally posts a thirst trap on Instagram, the answer is yes.

Rebecca Lehrer: Yes, but we thirsted. We thirsted. We reacted.

Amy S. Choi: Respectfully, very respectfully.

Lisa Ling: He’s a cute guy. He’s a tall drink of lemonade. So neither of our parents were around, I think, as much as we would’ve liked. And they’re so opinionated about how we are raising our kids, and neither of them are shy about divulging what they think we should be doing-

Amy S. Choi: Never.

Lisa Ling: … in raising our kids. And so there’s so many times when Paul and I are just like, “Why didn’t you do that when we were kids?” And so that’s really hard sometimes and we’ve gotten into some big fights with each other, with them, and we’ve both stormed out of the room or we’ve just become apoplectic, so yes.

Amy S. Choi: And Paul’s also… He’s got 50% Korean rage, so it’s just like it’s embedded in there. I got it.

Lisa Ling: I would say it’s 75% Korean rage.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, 75%. We’re inching closer to the boiling point.

Lisa Ling: And particularly when it comes to things that may have a direct relationship with his upbringing, because when you’re a young kid and you harbor those feelings of abandonment or rejection or whatever, and it continues to go unresolved for your whole life, it can manifest itself in very negative ways. And I think this is particularly applicable in Asian communities where there isn’t as much communication or affection. It’s really hard. I think that’s one of the reasons why it really frustrates him even more than it frustrates me, and it frustrates me.

Amy S. Choi: Wow, Lisa. This is the past 10 years of therapy just bubbling. I will say, so my older sister, who basically raised me because I had a very similar situation where grandmothers would kind of pop in and out of our lives from Korea and kind of rotate around the cousins’ houses taking care of us when there was the most need. But my sister, who’s six years older, by the time she was 12, was responsible for me. And she’s exactly your age. She just turned 50 this summer. And I think for both of us, I watched her go through this huge exploration, which I have learned that Paul has done, as well.

But it’s almost like you don’t even know, and I’ll speak for her and me, is that you don’t even know what you thought you needed or that you missed until you have children of your own. And then you’re like, “Oh, fuck. What are these feelings? Why do I feel this rage? What is happening here?” And this act of kind of re-parenting yourself and then while also trying to learn how to be the kind of parent you want to be to your kids is wild.

And I just feel like that act of being like, “Oh, this is actually what I want,” or “This is what I need and how I want my family to be, but oh, shit, I have so much healing to do because there’s still a little kid inside of me that didn’t get the things that I now am seeing that I missed or that I wanted.”

Lisa Ling: Well, this is why it’s so important, and I’m so glad that we are having so many open discussions about generational trauma because I think it’s easy for us as parents to… And because we’re still harboring so much of that resentment about what we didn’t get-

Amy S. Choi: Because we’re still people, too.

Lisa Ling: Exactly. And in some ways we are still stunted, as children. Because we didn’t get those things that we really needed, and it didn’t resolve, it sort of festers for so long. And so Paul and I have done a lot of healing over the years, and we’ve both come to a place where we don’t just think about the issues of abandonment and the lack of affection that we experienced from our own parents ourselves. We think about, and I’m going to get very emotional here, how much our own parents needed that.

And I think the reason why they were unable to show it to us is because either it wasn’t part of their culture or they didn’t have models for it themselves. And so, over the years, Paul and I, where we had these resentments for our parents, what they weren’t able to provide for us, we have both transformed and really started thinking about trying to offer that kind of affection to our parents because we know that they didn’t have it either.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, Lisa.

Lisa Ling: And in some ways, we are becoming the teachers that even I think our parents still need. And it’s really made our relationship with our parents and our family just so much deeper. Plant medicines have helped. I’ll be honest with you.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, no, I’m crying. I’m crying. I am so in awe, Lisa. Here I am, wiping tears. I’m going to try not to snot all over my microphone, but I just think that that level of curiosity and compassion is what I feel like I’ve been trying to get to for a long time.

Lisa Ling: It’s hard.

Amy S. Choi: It’s so nice to see that you got there.

Lisa Ling: It is really hard because so many of us just have these deep scars, and it’s impossible to think about our own parents not as our parents, but as a similarly stunted child who didn’t get what they needed from their parents. And when you really stop and think about it, our parents didn’t just have parents that weren’t able to show affection, they went through wars, they went through poverty. They went through and experience things that, in our wildest dreams, we can’t even imagine. And so that’s another layer of trauma and closed-offness that they are harboring inside of them.

And again, plant medicine’s really helped us see this, that we all need healing and that the resentment directed toward our parents is sometimes really misplaced because it’s not their fault and it’s not their parents’ fault. It’s this trauma that has lived with us intergenerationally that we can’t pinpoint. But it makes sense that if you don’t have a model for how to do it, how would you ever know how to do it?

Rebecca Lehrer: Also, how could you process so much of the stuff that they experienced? There’s no processing the wars or like, “Oh, all my aunts were murdered.” You have to compartmentalize that stuff.

Lisa Ling: You have to shut down-

Rebecca Lehrer: … in order to keep living.

Lisa Ling: They’re doing that, and they do that to try and protect their kids. I came to this country because I want to give my kids and future generations a better life, but I could never talk about it because I don’t want to think about it because it’ll take me to a dark place. I’ll go into a deep depression, but I also don’t want to burden my kids with this trauma that I’m still holding.

Rebecca Lehrer: I also think there’s just so much loneliness. I’ve observed this in the immigrant generation is I think, this makes me really sad, but I think they feel really alone in this world because in order to make their lives work or had made it possible for our lives, there’s a sense of being so self-reliant and then distrust of anyone else being able to get shit done. And I think that’s just so painful.

Lisa Ling: Well, it’s so multifaceted because that generation, their eyes have seen so much, right?

Rebecca Lehrer: Yeah.

Amy S. Choi: Yeah.

Lisa Ling: And you can bury it, but you can’t pretend that it doesn’t exist. And sometimes it manifests itself in ugly or angry ways, on top of the fact that there’s a lot of pride in Asian communities, but so many immigrant communities. There’s a whole concept of saving face. And so the idea that you are not maintaining a certain life, I mean, I think that’s one of the reasons why Asian culture is so materialistic.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, my God, we just had this conversation.

Lisa Ling: It’s a way to show what I’ve earned and where I’ve come, and it’s-

Amy S. Choi: Validate all the things that you have sacrificed in your Fendi bag.

Lisa Ling: Absolutely.

Amy S. Choi: Well, here’s a tactical question. You’ve done so much work and so much healing and created so much compassion and empathy in your home. Did either of you talk to your moms about it? Was this a conversation that was had in that direction, or was it just an acceptance and a reforming of family bonds?

Lisa Ling: Oh, no. We’ve talked to our parents. In fact, we talk a lot now, and in the case of my mom, who left it when I was seven, my sister was four. It’s like I grew up thinking, how do you leave kids when you’re that age? I was with my dad and my grandma and we were in a stable community, and my mom was not stable at the time, and I had that resentment. I was holding that resentment for so many years until I had a plant experience.

Rebecca Lehrer: My God.

Lisa Ling: And, rather than going back to my childhood, it’s going to sound a little esoteric, but I have to talk about it because it was so profound. Rather than going back to any episodes in my own childhood, I went back to my mother’s childhood. I relived aspects of her childhood, and they were so hard, and they were so dark and so sad that the next day I came home from that experience, I went to my mom’s house and I held her like she was a child, and I told her that I will take care of her because nobody had ever told her that in her entire life. My mom and so many immigrants, they’re just hustling. They’re just hustling. They’re just trying to survive.

Amy S. Choi: Everyone just wants to be taken care of, actually.

Lisa Ling: Yes, yes.

Rebecca Lehrer: Now you have a child the age that your mom left, right?

Lisa Ling: Yeah.

Rebecca Lehrer: When you look at your baby, well, you’ve had two. Go through that. So the youngest one is that age. Oh, I guess they’re probably the same distance that you and Laura are.

Lisa Ling: Yes, my sister. Right.

Rebecca Lehrer: So when your elder was seven and your younger was four, what happened in that moment for you? Was there an awareness of, oh, this is a Rubicon we’re crossing? What was bubbling up for you when your kids were suddenly the age when your mom did-

Lisa Ling: Dude.

Rebecca Lehrer: You don’t have to go there.

Lisa Ling: Well, let’s just say when you’re one of the few Asian kids in an all-white community, upwardly mobile community, but you’re pretty lower middle class, you just want to pretend that everything’s fine and that it’s all good. And when you are the only kid whose mom isn’t at the parent-teacher conferences or at any of my activities, you just become good at painting a picture. “Oh, she’s at a work thing,” or “She’s not able to make it.” Meanwhile, she’s living in another city.

But what I came to realize, I was hiding so much as a kid, is that we all hide so much from other kids. Some of the kids that I went to high school with who I thought had everything, the perfect lives, the perfect homes, the perfect cars. Later on when I would catch up with them and they would tell me, “My dad was cheating on my mom,” or “My mom was an alcoholic.” I was like, “Oh my God, I thought you had the perfect life.” And that has really allowed me to feel so much more compassion for human beings.

Rebecca Lehrer: Totally. Also, you have no fucking idea.

Lisa Ling: No idea.

Rebecca Lehrer: Especially when you’re going through things. In my life there’s been, let’s just say, some acute trauma moments where let’s say somebody died and then you have to go get something because you’re a human being who’s still alive, like go to the grocery store. And it’s the fog of that, and you’re just watching other people shopping who probably didn’t have somebody die hours before. And you’re like, “Wow.” Whenever I’m shopping on a normal day, I have no idea who else in this store, who, working at this store, anybody, what is happening in their lives right now. I have no idea. And if I can have that, give people grace or have that compassion in the world. You can say no to assholes while still giving a little more of a buffer for grace, because there probably is somebody walking in the grocery store who is dealing with that.

Lisa Ling: Yeah. And, Rebecca, that’s one of the reasons why in my work as a journalist, it’s been so important for me to highlight people or communities that you may think one thing of, but really never taken the time to understand or get to know. And so often, because we’ve covered so many marginalized communities or communities that might be considered sort of outsiders, so often so many people talk about these moments in childhood when something happened, some kind of trauma or some abandonment or some fight or something that happened that just never really resolved itself.

And that kind of sent them off onto a path that was unfamiliar. It makes me just think about how important it is to try and encourage each other to try and look to go deep, as hard as it is. And so fortunately, we are living in a time when there’s an elevated consciousness about this, about dislodging those deeply held traumas that so many of us are carrying from childhood, and bringing them to the fore, no matter how difficult it is, and trying to finally find some resolution and healing.

Rebecca Lehrer: What if I was like, “I’m so traumatized by people’s Instagram comments, the misuse of trauma also.”

Lisa Ling: Totally.

Rebecca Lehrer: It’s such a funny… You’re like, “No, no, no, that’s not it. That ain’t it.”

Lisa Ling: Exactly.

Amy S. Choi: I just think that there is something also, and another ongoing theme is just reminding ourselves, because Americans are often convinced that we invented the thing or that this is a new experience. And I think what you’re talking about here, especially in relationship to intergenerational families and how to bring families closer, this is where I bring up the Joy Luck Club, sorry to be the middle-aged-

Lisa Ling: Best movie ever.

Amy S. Choi: …who does this. Best movie ever. But that idea of stairs, that I’m a step and my children are part of my staircase, and so are my mothers and their mothers and their mothers and their mothers, and just remembering that we are bound to all of those generations forward and back, and we can decide how we want to reshape it. But that does not mean that we can exist separate. And I think that’s a very not American idea or something that we reject so thoroughly that it actually does so much damage to us because we are constantly thinking we can just reinvent ourselves and we can, and we don’t reinvent ourselves from a blank slate.

Lisa Ling: Absolutely.

Rebecca Lehrer: This is something though, on a sort of lighter note, and I say this as the only non-Chinese or Korean person here-

Lisa Ling: What are you talking about, lighter?

Rebecca Lehrer: Sort of lighter, okay.

Amy S. Choi: This is light. This is every day.

Rebecca Lehrer: We have actually had, speaking of Chinese Koreans, Akwafina on our show several times, and her grandmother actually giving some dating advice, and we’ve asked many people in our community over these last many years, 10 years of The Mash-Up Americans, what dating advice did you get from your immigrant parents? And most of it’s racist, and this is racist, but positive, is that Korean parents, mothers, always say, “Marry a Chinese man because he’ll cook for you.” And so I wanted to explore that here. You did the reverse. How do you feel about that advice? Do you feel that that’s resonant?

Lisa Ling: Well, I probably didn’t have that experience because I am the woman who married a Korean man, because when my-

Rebecca Lehrer: Well, that’s because all the Korean women are with the Chinese men. You’re like, “I scored.”

Lisa Ling: Well, I had so… I had? I have so many Korean girlfriends. Most of my closest friends are Korean women, and they would tell me that they wanted to marry Chinese men because they took care of the women. And they told me not to date Korean men because I’ve always been, I don’t know why, attracted to Korean men.

Amy S. Choi: Because they’re hot.

Rebecca Lehrer: Because they’re hot and they’ve got that swagger. That’s why.

Lisa Ling: Yes. So I ended up with this guy, and when his mom found out that I don’t cook at all, again, she didn’t actually say anything. It was just like, “Oh, you don’t cook?” “No, I don’t know how to cook at all.” It was “Mmm.” It was like that, “Mmm.” I’m trying to get as low as she. “Mmm.” She was not happy that nobody was going to cook for her son, because in the beginning of our relationship, she would even call me and I would answer, “Hello?” And she’d go, “How is he?” Rather than, “How are you? What’s been going on?” It was just, “How is he?”

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, my God. My face is hurting from smiling.

Lisa Ling: Because the first son in Korean culture, he’s the falcon of the family. He’s the one on whom one should dote and take care and so on. So initially it was a little bit disconcerting, but I couldn’t lie and tell her I cooked when I burn scrambled eggs. So I think she was somewhat displeased by that, especially because when I first met her, and my mother-in-law has a very strong personality and is very opinionated.

Rebecca Lehrer: I want you to know that there was a question in our notes, which was, how do you live with your Korean mother-in-law? I didn’t write that. Amy did. Just for context.

Amy S. Choi: I wrote that. And, for the record, I don’t live with her. I have a Mexican mother-in-law, and that’s enough.

Lisa Ling: Right. Right, right, right.

Rebecca Lehrer: And she’s far away. She’s 1,000 miles away. Okay, go on.

Lisa Ling: So the first time I met his mom, he invited me to a family gathering, and I was feeling a little… It was my first time. It’s a house full of people.

Amy S. Choi: Korean people.

Lisa Ling: Korean people, all Korean people.

Rebecca Lehrer: Who it turns out both Lisa and I love Korean people.

Lisa Ling: Love. It turns out, love, and I’m like, you know, all my friends are Korean. I got this.

Rebecca Lehrer: You’re like yoh-boh-sayo.

Lisa Ling: Yeah, I had my whole… I bowed, annyeonghaseyo. The first thing that my future mother-in-law said to me, she didn’t smile. She took my hand and she said, “Have you accepted Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior?”

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, she’s that, she is.

Amy S. Choi: I knew that. I knew it was coming.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, wow.

Lisa Ling: And I’m rarely at a total loss for words. I mean, even in uncomfortable situations, I usually have a retort. I found myself just completely speechless. My mouth was dry. I’m like, “Oh my God. What am I going to say?”

Amy S. Choi: Korean people are so intense.

Rebecca Lehrer: But did she put bibles in your house everywhere in every drawer?

Lisa Ling: Oh, no, no. She gave me one later on. But anyway, so my response was, “I grew up going to church. Yes, I used to go to church every Sunday,” and then I just left it at that. And of course, I was met with, “Mmm” again. I got used to that sound, and I’m not even doing it justice. So that’s how my relationship with my mother-in-law started off.

Rebecca Lehrer: But you gave her grandkids.

Lisa Ling: Well, I did, but mind you, all my close Korean girlfriends warned me about the Korean mother-in-law. I mean, they warned me incessantly like, “Oh, my God, you sure you want to do this? You’re going to get a Korean mother-in-law.” And look, I’m a journalist. I can embed in any kind of community. And so for me, it was like, I’m okay. I can win people over. It’s what I do. I’m a kind person. And so when I was met with that first question, it was like, “Oh, shit. This is real.”

Rebecca Lehrer: You’re like, this is the warfare. I was not prepared for this.

Lisa Ling: Yes. And then followed by the “Mmm” after she found out I couldn’t cook for her son, that was just like, “Oh, my God, is this real? Is what my girlfriends, is what Alice and Shin and Cindy were telling me, is that real?” And it was real.

Amy S. Choi: So what would you say are the rules of engagement in your Chinese-Korean house and marriage? Because it feels like there’s a lot of levels here.

Lisa Ling: I mean, I do think that, if I were Korean, my relationship with my mother-in-law might be different. I think there are things about language that I just don’t understand that may have been more present had I been Korean, and I know that she and her husband would’ve loved for Paul to marry a Korean girl, just like my parents would’ve loved for me to marry someone who’s Chinese.

But I will say that, while I was initially spooked, and again, because my mother-in-law also just has a very strong personality, and at the time she was sort of incapable of not offering me suggestions, and just divulging her opinion, she has become one of my best friends, and I respect her so much. I respect her journey. I respect the life lessons that she bequeaths to me and to my kids. She’s such an amazing person who has accomplished so much, and I love her. Even though I don’t believe what she believes, I happen to have a pretty impressive biblical repertoire. And so when she comes at me with something-

Rebecca Lehrer: A Bible verse?

Lisa Ling: … that she thinks is Biblical, I have a retort very often because I’m familiar with much of the Bible, and I think she respects that I at least have the knowledge. It isn’t a decision that I’ve arrived at erroneously, and that I am a very spiritual person and that God is a very important person in my life. I just have a different path to God. I believe that people do have different paths other than that one path.

I mean, religion is still somewhat touchy in the household, but there is such a deep respect for the human and even the faith, because her faith has gotten her through so much. And so I really respect that relationship that she has with her faith. I mean, I truly love her, and I don’t just consider her my mother-in-law. I really do consider her my friend, and I call her about things. I ask her advice and-

Rebecca Lehrer: What do you call her? Not on the phone, but what name do you call her?

Lisa Ling: Well, I mean, before I had kids, I would call her Mom. But since having kids, they shortened. You say halmuni, you call a Korean grandma halmuni, but they call her Hammi for short. And so we all just call her Hammi. Everyone just calls her Hammi.

Amy S. Choi: I love Hammi and Coco names.

Lisa Ling: I know. I know, we have these little pet names.

Amy S. Choi: Really mashup. It’s so cute.

Lisa Ling: It’s so mashup.

Rebecca Lehrer: That’s so great.

Amy S. Choi: Okay. I have two final questions to wrap up.

Lisa Ling: Okay.

Amy S. Choi: So one of the great entry points into all of our lives, I think, of getting to know each other, and we think about this all the time, is just a gateway to everything is food, right?

Lisa Ling: Yes.

Amy S. Choi: One of our big questions, but not a question, it was a statement that was in our notes, was Chinese versus Korean. Go. And I’m going to say Korean wins here.

Lisa Ling: Oh, for sure.

Amy S. Choi: Not that it has to be a competition.

Lisa Ling: Well, as far as preference is concerned, I will always choose Korean food over Chinese because my body just craves fermented stuff.

Amy S. Choi: Me, too.

Lisa Ling: And I love the flavor of kimchi everything. Kimchi is my favorite thing. I dream about it. But Paul, who is Korean American, will always choose Chinese food.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, wow.

Amy S. Choi: Wow. This is just a very interesting thing we have going on here.

Lisa Ling: Always. Always.

Rebecca Lehrer: I did have some delicious naengmyeon last night. I was like, “I have a tummy ache. I’d like some cold noodles.”

Lisa Ling: It’s my kids’ favorite. In fact, both my kids. I, growing up, I hated smelling like Chinese food. I never wanted to eat Chinese food. I just wanted McDonald’s and spaghetti. But my kids both always want Asian food. They have a preference for Korean food, but they like Chinese food, too, and they insist on taking Asian food to school.

Amy S. Choi: Yes.

Lisa Ling: They’re proud of every aspect of their Asianness.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, my God. Wait, I had a dream about your daughter, Amy.

Amy S. Choi: My daughter?

Rebecca Lehrer: Mm-hmm. In relation to exactly this, which was we were explaining how different and wonderful it is to just be like, “That’s 30 years of people making this possible for you to then just feel fucking proud. There’s no noise about any of it.” And to even be like, “Wait, you were worried about that, Mom?” It’s so brilliant and cool.

Lisa Ling: Yeah, that seems wild.

Amy S. Choi: Wow. I have damp tissues just at my feet right now in my booth. But I think my final question, and I know this is Rebecca’s, as well, whenever we are in the presence of greatness, just you are a woman who has done so much with your life and your career and your personal life and gone through so many transformations, you’re a hugely successful mother of two young kids who are exactly the same age as my kids, actually, 10 and seven. And Rebecca has-

Rebecca Lehrer: Mine are seven and four.

Amy S. Choi: … two kids right up on the way, is just can you leave us with any tips as to just fucking how? Like how? How are we supposed to get how does it all work because-

Rebecca Lehrer: And just For context, I did have to go to an urgent care yesterday for something that was probably a panic attack.

Amy S. Choi: A stress-related panic attack. And it’s just we watch you navigate this world. We know it’s not easy, and we have worked with you. We have gotten to know you, and it’s just been so, so great, and we want to know how you do it so that we can do it, too.

Lisa Ling: Well, if for some reason I have conveyed to people that I know how to do it, then I have really fooled a lot of people because, oh my God, it is so hard. It is so, so hard. And that’s why I will continue to fight for moms and advocate for moms because it is so hard. I’m very lucky that I have a spouse that will do a lot of things that many male spouses refuse to do. I’m very, very lucky, and it’s still hard. And so to those moms who are shouldering everything, my respect knows no bounds.

I mean, the only thing I would say is don’t be afraid to ask for help. Because I think we, in our culture, when someone calls us a supermom, we kind of wear that as a badge of pride, when those are impossible expectations to uphold. They’re just impossible. And I would like us to just allow ourselves to be vulnerable and just say that I’m going fucking bananas and that I need help. Every single day, it’s a constant, like, “Lisa, you need to get your shit together today-“

Amy S. Choi: Totally.

Lisa Ling: Because it’s chaos all the time. And we are, no matter how supportive our husbands or our spouses, if we have them, are, we are still the ones who are maintaining all the schedules in our heads and making sure that this person is there and all that stuff. But just give yourself a break and don’t think you need to do it all and don’t be afraid to ask for help.

Rebecca Lehrer: I think the asking for help, which is a great way to wrap this idea of what we’re talking about in an intergenerational home, and also some of the stuff that we come up against as mashups, as first generation and as women. And then in the context of America, this sense of self-reliance, which you can’t rely just on yourself in the world. And I think I’m not that good at asking for help. I’m very good at providing help, but I think that it’s a good reminder.

Lisa Ling: And it’s okay when you borrow things from other cultures. Ours isn’t the only way. It shouldn’t be considered to be taboo or whatever.

Rebecca Lehrer: Yes.

Lisa Ling: In some parts of the world, they actually do things better.

Rebecca Lehrer: What? Oh, my God.

Amy S. Choi: How dare you, Lisa Ling.

Rebecca Lehrer: Lisa Ling.

Amy S. Choi: Lisa, we love you. Thank you so much for being here.

Lisa Ling: You guys, love you, too.

Amy S. Choi: This was so, so great.

Lisa Ling: This was so fun, and now I need to go into therapy again, although that was so good. That was so good.

Amy S. Choi: Wow. The way that the entire floor of my booth was just like a foot-high puddle of snotty tissues at the end of that conversation.

Rebecca Lehrer: She was surprised. Lisa was surprised. Yeah.

Amy S. Choi: Oh, my God. Anyway, so was I. So was I, is what I’m going to say. And I’m just so grateful that she shared her story because I think I’m turning a new leaf. I mean, maybe next year, for me, it’s like Judaism and a lot of psilocybin. What do you think? Do you think it goes together?

Rebecca Lehrer: You know Ram Dass was a Jew. Love this for all of us.

Amy S. Choi: Next week we’ll be joined by our old pal, Rainn Wilson. Maybe it surprises you that he’s our old pal, but he’ll be coming to chat with us about all things spiritual and how to find your spiritual path in a world that sometimes feels like basura. You will not be surprised to learn that we laugh a lot, too.

Rebecca Lehrer: Make sure to catch the rest of The Ultimate Guide to a Mash-Up Life every week this fall, and like and follow The Mash-Up Americans wherever you get your pods.

Amy S. Choi: And tell your friends.

Rebecca Lehrer: And if you haven’t signed up for the newsletter, do it. mashupamericans.com/subscribe. Love you.

CREDITS:

This podcast is a production of The Mash-Up Americans. It is executive produced by Amy S. Choi and Rebecca Lehrer. Senior editor and producer is Sara Pellegrini. Production manager is Shelby Sandlin. Thanks to DJ Rob Swift for our theme song, Salsa Scratch. Additional engineering support by Pedro Rafael Rosado. Please make sure to follow and share this show with your friends. Bye.